Photo: guard on Death Row.

Meeting

Adisa on San Quentin's Death Row

by Tom Kerr

Held up by lackadaisical guards, Adisa Kamara (a.k.a. Steve Champion) arrived a half-hour late to our long-anticipated meeting. The California Department of Corrections grants extended visits to anyone who travels over 250 miles, and I had traveled, in April 2005, three thousand miles, from Syracuse, New York, to meet my friend. I waited locked up in one of fifteen three by six foot steel-mesh cages that now constitute San Quentin's Death Row visiting room.

|

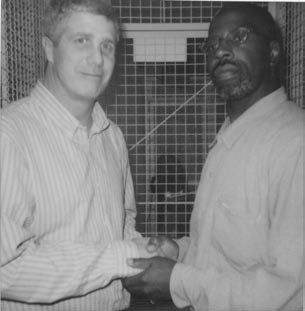

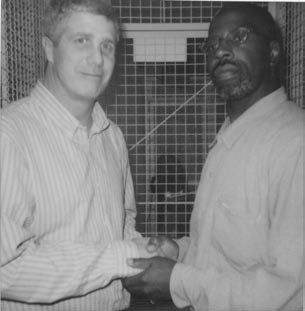

| Tom and Adisa at San Quentin. Photo: guard on Death Row. |

Directly behind me, in a booth designed for visitors whose prisoner was not, currently, allowed contact visits (the privilege is stripped from men in the "hole"), a woman, four-year-old boy in tow, sat down to her visit. Six or seven such booths lined the wall, and through the murky plexiglas in the woman's booth I could only vaguely make out the figure of the man on the other side, leaning forward on his elbows, talking loudly, straining toward the woman and boy. As soon as the boy realized he could not get at his father, whose predicament he could never fathom, the boy began to bawl inconsolably. The mother continued to talk through the plexiglas while trying in vain to comfort her son.

About fifteen minutes into my half hour wait, a guard escorted a relatively young man - many of the inmates I saw were graying - into the cage on my immediate left. Short and thin with a thick head of black hair and wearing sunglasses, he stood perfectly erect, waiting and watching for his guest to arrive. He and I studiously avoided direct eye contact, even though less than four feet separated us. He looked through me, past me, around me, effectively but without malice disappearing me, and I him. Five, maybe ten, minutes passed before his mother, wearing a colorful spring dress, was admitted to his cage. Outside the prison, this woman had helped me understand the bewildering/ chaotic protocol for visitors holding appointments. Now warmly embracing her son, who had taken his sunglasses off, here she was again, a breath away from me in this most intimate confinement. As I would learn from this Iranian mother at the break, she had been making the round trip from Los Angeles every week, and then, as visiting rules tightened, every other week, for eleven years. After thanking me for "visiting these men," she told me her son had been framed for a neighborhood murder because he was "the little Iranian kid nobody liked," and she was appealing to the Innocence Project for help.

While I waited eagerly to meet Adisa, with whom I had been corresponding for three years, working as his editor on a collection of essays called One Day Deep: Meditations on Death Row, several other condemned prisoners were marched in and out of the visiting area. Each time the door of the prison's inner sanctum opened, I paid close attention, not sure I would recognize Adisa from photos on the web or from the picture he had sent.

What I saw, then as I waited, was a surreal procession of condemned men, each groomed immaculately, each dressed impeccably in highly-pressed blue denim, each holding his shoulders and head high, and each invariably greeting one or more of the men who had already been placed in a cage. While we are constantly and in myriad ways reminded that only devils end up on death row, and without doubt many have murdered and otherwise wreaked havoc on others, this was surely a procession of angels through hell.

At last, Adisa (which in Swahili means "one who will teach us") emerged from the tunnel and was locked in the cage with me and uncuffed. In our ensuing three and a half-hour meeting, it became clear that California was preparing - 24 years is a long time to prepare - to execute a man who is not the boy who was convicted in 1980 of a double homicide, on circumstantial evidence, in a county reeling at the time from an epidemic of Crip-Blood gang violence. Our animated conversation confirmed what I already knew from his writing and correspondence. Through twenty-years of self-education, collective study, deep meditation, discipline, and active involvement in affairs of the world via publishing poems and essays, Adisa had become a highly principled, peace-loving, social activist deeply committed to understanding and transforming the socio-economic and political conditions that foster gang culture and black on black crime.

I had come to San Quentin for a writer and his editor to establish the trust required of a project in which the writer was pouring forth heart and soul. I met a man who, but for our radically

|

What

You Can Do

• Join PEN's American Center campaign for clemency/commutation for Adisa and other PEN Prison Writing Award Winners at www. pen.org/page.php/prmID/152(Prison Writing Program under the Programs Link). • Fight the death penalty (such as its reinstatment in New York) with Human Rights Watch (hrw.org/doc/?t=usa_deathpenalty ) and Amnesty International (http://web.amnesty.org/pages/deathpenalty-index-eng), which keeps track of execution dates, past and pending. |